Phytoplankton — microscopic plant-like organisms — are the foundation of the marine food web, sustaining everything from tiny fish to multi-ton whales while also playing a critical role in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Accurately monitoring Earth's phytoplankton is essential, especially when it comes to understanding the effects of global warming or possible carbon-removal initiatives. The ability to track phytoplankton has largely depended on space satellites observing the sea surface.ÌýYet, phytoplankton can grow below the surface where satellites cannot detect them, leaving a significant gap in how we monitor one of Earth's most important primary producers, which are organisms that carry out photosynthesis and form the base of the food web.

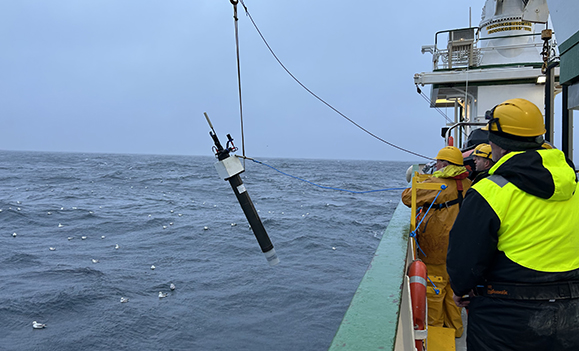

Researchers at ºÚÁϳԹÏÍø are changing that with the help of a growing global network of underwater robots known as Biogeochemical-Argo floats. These devices travel below the ocean's surface and measure phytoplankton where satellites cannot. As part of the , the floats are deployed across the globe in an international effort to monitor the ocean's biology, geology and chemistry.

UncoveringÌý"hidden" phytoplankton

Ìý

In a , scientists used data from these Argo floats to calculate how much phytoplankton biomass is on Earth: about 343 million tonnes or roughly the equivalent of about 250 million elephants.

At least half of that is not observed by space satellites.

Adam Stoer, a graduate student in Dal's Department of Oceanography and lead author of the paper, says the research represents an important advance in tracking the world's "hidden" phytoplankton and is needed to better track the effects of climate change on the ocean.

"What our paper highlights is that this global fleet of robots will be incredibly valuable for monitoring Earth's phytoplankton as a whole, so we can understand how they might respond as the ocean continues to warm," he says of the work being published in the journal, PNAS.

"This fleet of robots has grown to a point where we can quantify how much phytoplankton there are and monitor where they are and when they 'bloom,' which is becoming increasingly necessary given how quickly the climate is changing our oceans."Ìý

Researchers at sea.

The Dalhouise researchers used about 100,000 water-column profiles from the floats to describe Earth's phytoplankton carbon biomass and its spatiotemporal variability. The floats measure phytoplankton below the sea surface year-round and across the whole ocean, which wasn't feasible before they became available.

"This study highlights the critical role of Biogeochemical-Argo floats for improving our understanding of global phytoplankton carbon biomass, revealing that about half of the biomass lies below the depth of satellite detection and demonstrating the limitations of using surface chlorophyll-a as a proxy for carbon biomass in monitoring ocean health and climate change impacts," says Blair Greenan of the Ocean Monitoring and Observation Section of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Documenting a mismatch

While researchers routinely go out on research ships to collect samples of seawater, quantifying phytoplankton biomass at a global scale is not possible this way. There are simply not enough people, ships or funds to collect enough samples given how massive the ocean is, the authors say.

Researchers have long relied on satellite ocean colour observations to describe phytoplankton at a global scale. From these satellite observations, chlorophyll-a — a commonly used proxy for carbon biomass — can be estimated. However, it is an imperfect way to represent carbon biomass because phytoplankton's growing conditions (e.g., sunlight availability) drive large variations in the ratio between the two.

"Another important outcome of this study is that we documented the substantial mismatch between the seasonal cycles of carbon biomass and surface chlorophyll-a. This decoupling is present in two thirds of the global ocean," says Dr. Katja Fennel, departmental chair of Oceanography at Dal and senior author on the study.ÌýÌý