Sarah Fortune was high atop the fly bridge of a snow crab boat, searching for endangered North Atlantic right whales, when she and research colleague Heather Foley noticed something odd about one of the animals they were tracking northwest of P.E.I. in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Dr. Fortune, an assistant professor in Dalhousie's Department of Oceanography and the Canadian Wildlife Federation Chair in Large Whale Conservation, saw the whale was behaving strangely. So the pair grabbed some binoculars, started taking photos to document the case, and PhD student Jay Kirkham flew a drone above it to gain a better understanding of what was happening.

They quickly realized the whale — one of only about 340 remaining in the world — had a long line of fishing rope coming out of its mouth and trailing many lengths behind it. It also looked to have a fresh wound on its tail.

"Finding this whale entangled in fishing line shows how important it is to remove lost fishing gear in protected areas," says Dr. Fortune, who adds that her crew hauled up lost snow crab pots earlier in the cruise.

"It also makes clear the need to modify fishing gear, particularly in offshore waters where right whales and these kinds of gear may overlap. And the more whales we lose to entanglements, the more difficult it becomes to sustain this species."

They decided to suspend work they were doing on zooplankton at that site so they could follow the whale, who they learned was an unnamed 13-year-old male identified as #4042. They spent hours trailing behind it for about 20 miles until darkness closed in and they had to end their pursuit.

A danger to whale health

The team collected data on the whale's behavior, location and heading to provide to the Campobello Whale Rescue team rescue group that hoped to get out and try to remove the line. The whale had been seen just seven days earlier on July 8 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and was not entangled at the time.

Rhyl Frith, who is with the Canadian Wildlife Federation and is starting her MSc in Oceanography at Dal this fall, says she and her colleagues counted at least six body lengths — or roughly 60 metres — of line following the whale under the water's surface. She says it appeared to be partially weighted much like the line used in the crab fishery.

It wasn't clear if the line was impeding his ability to eat, but it could restrict the whale's filtering capability and divert it from its drive to find its primary food source, tiny crustaceans called copepods.

"If the whale is entangled, they're under an incredible amount of stress and even if they are physically able to feed, their focus could be shifted more from feeding to a flight or fight stress response as they try to escape," says Frith, adding that the rope may have sheared off skin near the whale's fluke and peduncle, the area near the tail.

"The whale was thrashing its fluke on the surface, swimming fast, and repeatedly going on very shallow low-fluking dives, so it seemed like it was struggling."

Unfortunately, the whale hasn't been spotted since despite searches by vessels and planes. A marine rescue group hopes to attempt a disentanglement if it is found.

Learning more about right whale behaviour and feeding habits

The encounter occurred during the first of three different missions Dr. Fortune is undertaking this summer to affix the suction-cup attached bio-loggers to four different species of whales to learn more about their underwater behaviour, feeding habits and better protect them against their greatest threats. The tags will capture sound, video and three-dimensional movement of the whale, temperature and along with GPS data.

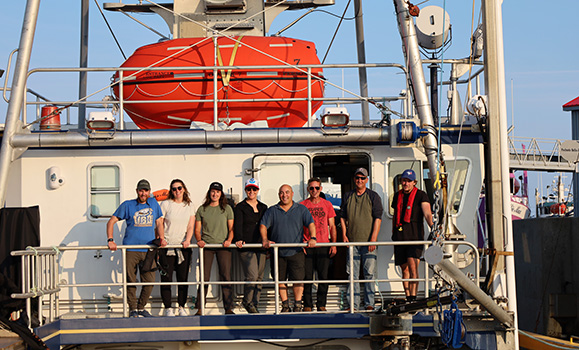

The team (pictured above) managed to successfully attach tags to four right whales, an impressive feat that could yield unique information about the feeding habits, nutritional well-being, movement and the nighttime and daytime activities of the imperilled species.

Right whale numbers have been declining since 2011, with data from the New England Aquarium indicating entanglements in fixed fishing gear as the primary cause. It shows that more than 86 percent of right whales have been entangled at least once, some as many as nine times. Whale #4042 has been entangled at least four other times before this event, which scientists say shows the need for stronger measures to protect the critically endangered species.

Frith, who has been working on entanglement risk reduction strategies for right whales for years, says the experience will stick with her for a long time.

"Up until this trip, I had never seen a right whale and had done all this work to help keep them gear free, so seeing one that was entangled and clearly struggling made what I've been doing in the past few years so much more meaningful," she says. "It will stay in my mind forever. I think the work being done now to prevent this is so important."