Two şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřmedical students delved into the difficulties that people with intellectual disabilities face when seeking health care, in a two-way information exchange facilitated through the medical school’s Service Learning Program.

Alexandra Munroe and Nick Cochkanoff teamed up to work with the Regional Residential Services Society (RRSS), a non-profit agency that provides community-based supports in homes and apartments to 165 adults with intellectual disabilities in the Halifax Regional Municipality. The participants’ disabilities are associated with autism, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and many other health conditions.

Both students had worked in RRSS-operated group homes before entering medical school, although they did not meet each other until their first year in the medical program. When they saw that RRSS was one of the agencies involved in the Service Learning Program, they decided to work together on a project.

“From our previous work, we had the sense that people with intellectual disabilities might not be receiving the best possible medical care,” says Nick. “We wanted to learn directly from them what their experience was like, while sharing information with them they would find useful.”

is part of , the school’s five-year plan to continue to achieve excellence in medical education while serving and engaging the broader community. Run out of the Global Health Office, the program matches second-year med students with community partners to give students a taste of the wider community’s needs and resources to inform their future practice.

Challenging assumptions

The students’ first step was to meet with RRSS’ senior director Ruth Wilkie to discuss how they could best contribute.

“We originally thought the students could develop a document about key issues in providing health care to people with intellectual disabilities, to share with their peers in medical school,” notes Wilkie, “but we could see how competent, keen and confident they were and knew they would excel in a more dynamic involvement with our residents.”

This is how the idea of developing a series of health education sessions for residents emerged. To ensure their efforts would be on target, Munroe and Cochkanoff met with the RRSS Residents’ Council to discuss their interests.

This is how the idea of developing a series of health education sessions for residents emerged. To ensure their efforts would be on target, Munroe and Cochkanoff met with the RRSS Residents’ Council to discuss their interests.

“We thought they would want us to cover a range of basic health topics,” recalls Munroe, “but they wanted to know about much more complex issues such as stress, mental health and grief, healthy eating and physical activity, and the complications and side effects of medications for common conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.”

Cochkanoff and Munroe prepared and delivered three very well-attended education sessions on these topics with residents from the 55 RRSS group homes around HRM. The session on healthy eating and physical activity was the most popular.

“The residents were really engaged in the conversation, they had a lot of personal stories to share and a lot of questions,” says Munroe. “The experience really drove home to us how important it is for health professionals to recognize that difficulty speaking, for example, does not imply difficulty hearing or understanding—so don’t make assumptions about what people understand, what they care about, their capabilities or their health goals. Everyone is an individual and needs to be treated as such—there is no blanket, one-size-size-fits-all approach that’s going to work for everyone.”

What makes a good doctor?

One of the most interesting questions that came up in the discussions was, “What makes a good doctor?”

“Participants spoke about how frustrating it is when doctors pose questions and provide information to their caregivers, rather than to them, even when they are right there in the room,” says Cochkanoff. “It makes them feel as if their opinions or ideas do not matter to the physician, and it makes it harder for them to ask questions, as they feel they will not receive an answer.”

Steven Ingalls, chair of the RRSS Residents’ Council, agrees. He says one of the biggest challenges people with intellectual disabilities face when trying to get medical care is just that tendency. “Doctors ask staff what is wrong with us when they should ask us,” he says, adding that the Residents’ Council would be very happy to have the students come back to talk to the residents in the future.

Inspiring future physicians

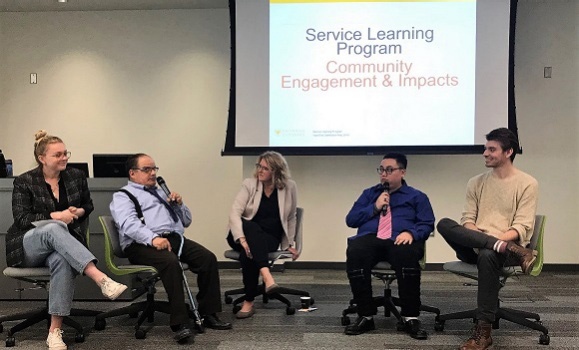

Cochkanoff and Munroe teamed up with Wilkie, Ingalls and another RRSS resident to share their experience with other medical students at a year-end event attended by all of the community agencies and students involved in the Service Learning Program this year.

“We hope other medical students will pick up where we left off and continue working with RRSS through the Service Learning Program,” says Cochkanoff. “You gain so much more appreciation and understanding when you go into a room and ask people directly about their experiences than you could ever learn in a lecture.”

Ruth Wilkie hopes that her organization’s involvement in the Service Learning Program will inspire at least one future physician to take a strong interest in the unique needs of people with intellectual disabilities.

“We have very few doctors trained or specializing in providing care for people with intellectual disabilities,” Wilkie says. “If this partnership with şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřMedical School could ignite even in one person a flame, a passion, a desire to do more for people with intellectual disabilities… it would so exciting to see someone focusing on this and stepping up to be a champion.”