Since the 1970s, Dr. Jock Murray has been collecting stories about the early days and ongoing evolution of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School and shaping them into a comprehensive history.

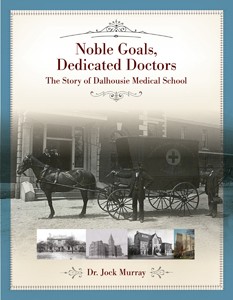

His years of dedication have culminated in , published by Nimbus in December 2017 ÔÇö just in time to kick off the year of celebrations marking the medical schoolÔÇÖs 150th anniversary in 2018.

His years of dedication have culminated in , published by Nimbus in December 2017 ÔÇö just in time to kick off the year of celebrations marking the medical schoolÔÇÖs 150th anniversary in 2018.

ÔÇťItÔÇÖs important that we know how we got to be where we are now, to understand how things have changed,ÔÇŁ says Dr. Murray, an alumnus and former dean of medicine at Dalhousie, and a neurologist known around the world for his contributions to MS treatment and research. ÔÇťThereÔÇÖs a tendency for people in any time to assume things have always been the way they are.ÔÇŁ

But the institutions we cherish today did not spring from the ground fully formed. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° (which marks its own 200-year milestone in 2018) and its medical school were born slowly, and sometimes painfully, from the vision and sheer determination of a few.

It started in an attic in a time of ÔÇťquackeryÔÇŁ

The original ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°College, established in 1818, was located on the Grand Parade where Halifax City Hall now sits ÔÇö but for years hosted a post office and a pastry shop rather than an eager student body. The medical schoolÔÇÖs earliest facilities (in 1868) were in the attic of this building, accessible only by ladder.

The original ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°College, on Halifax's Grand Parade, housed the medical school in its attic.

ÔÇťIt was not easy to convince ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°College to open a medical school,ÔÇŁ recounts Dr. Murray. ÔÇťThe college was barely on its feet in the 1860s and its leaders knew a medical school would be costly. Plus, there was no general hospital for hands-on practice with patients, no anatomy act to allow dissection of bodies for learning purposes, and little understanding even of the importance of medical education itself.ÔÇŁ

This lack of appreciation for medical education isnÔÇÖt as surprising as it might seem. Physicians of the time were not respected professionals; in the 19th century, medical science was just beginning to have an influence and much therapy was still based on the ancient theories of balancing the four humours (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile).

Treatments often involved bleeding patients with lancet or leeches and administering foul concoctions to purge them of ÔÇťexcess bile.ÔÇŁ In the eyes of their patients, physicians offered little more than the medical ÔÇťquacksÔÇŁ of the time ÔÇö frauds who lacked any real training but postured as doctors and offered miraculous elixirs for sale to a desperate and gullible public.

Dr. Tupper saves the day

It is thanks to the tireless and determined efforts of Dr. Charles Tupper that ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°College eventually agreed to establish a medical school ÔÇö and the City of Halifax a general hospital (at a time when there were few facilities besides ÔÇťthe Poor House,ÔÇŁ a dispensary and a facility known as Bridewell that housed sick prisoners and the destitute).

Dr. Murray signs copies of his new book.

ÔÇťDr. Tupper had received his medical training at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, which had developed a rigorous model of university ÔÇö and hospital-based medical education that was far ahead of its time,ÔÇŁ Dr. Murray explains. ÔÇťOther cities were following this leadÔÇŽ the medical schools at McGill, QueenÔÇÖs, Harvard and Philadelphia were based on the Edinburgh model, as were others around the world. Dr. Tupper wanted the same for the Maritimes and used his considerable influence as Premier of Nova Scotia to champion the cause.ÔÇŁ

Tupper ignited the enthusiasm of a small group of physicians and surgeons who, in 1867, gathered together and agreed to form a medical faculty. The self-declared faculty members ÔÇö Drs. Alexander G. Hattie, William Slayter, John Somers, Alexander P. Reid (who became the first dean), Edward Farrell and Alfred Woodill ÔÇö petitioned DalhousieÔÇÖs Board of Governors to accept them as such.

The board voted unanimously in favour ÔÇö albeit with less enthusiasm ÔÇö in February 1868. In a letter to the Medical Society, they wrote that ÔÇťthis Board did not feel justified in refusing the offer of the gentlemenÔÇŽ (we) see no sufficient reason for postponing further actionÔÇŽÔÇŁ

Within six months of its first meeting, the new faculty had designed its courses, recruited a full roster of instructors, secured facilities, and begun advertising for students. Fees were $6 per course and a dozen brave souls signed up to begin on May 4, 1868.

The stage is set for rapid advances

It was a bit of a bumpy start for the earliest classes of medical students who, until the Anatomy Act was passed in 1870, would venture forth under cover of darkness to secure cadavers from the Poor House by means of bribing the officials. Once concealed in body bags, the students would cart the corpses back to the college and haul them up the ladder to the attic. It is no wonder other students and faculty complained about the stench, as there was no embalming fluid and no ventilation.

Soon there was an anatomy act and a general hospital (which became the Victoria General), and the road to becoming a qualified physician became a little smoother. The stage was set for rapid advances in patient care, medical science and medical education.

ÔÇťMedicine was evolving rapidly and this was reflected at ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School,ÔÇŁ notes Dr. Murray. ÔÇťAdvances such as anesthesia, antisepsis, vaccines, effective new medicines and the microscope transformed medical and surgical practice. Now, treatments were based on science and achieving vastly superior results. All of these advances were adopted and taught at the medical school, which played a key role in the rise of medical professionalism.ÔÇŁ

Altruistic physicians and professors

As today, the early faculty members of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School took tremendous pride in their role of educating excellent doctors for the communities of the Maritimes (and Newfoundland, as well, until the 1960s when Memorial University established a medical school).

In spite of their skill and pride, physicians were not affluent prior to the advent of Medicare ÔÇö only about a third of patients were ever able to pay their medical bills. Physicians who taught at the medical school took it one step further ÔÇö not only did they often provide care to patients free of charge, they also often gave up their teaching salaries at the university to cover expenses and some of their studentsÔÇÖ tuition fees. At one point in time, faculty even funded the construction of a pathology addition to the medical school out of their own pockets.

ÔÇťThe physicians survived on their private practices,ÔÇŁ notes Dr. Murray. ÔÇťAn appointment at the university was to do with the honour of the association and opportunity to contribute to the next generationÔÇŽ feelings that persist today.ÔÇŁ

The building now known as the Clinical Research Centre was constructed as a public health clinic and key medical school facility in the 1920s with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. Shown here, the Class of 1932.

Promoting medical education for women

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School was far ahead of its time in welcoming women into the practice of medicine. In the 1880s, medical schools around the world were refusing entry to women, but ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°voted unanimously in 1881 not just to accept women into the medical school but to outright encourage them.

ÔÇťThe social norms of the time were such that many felt it was not ÔÇśappropriateÔÇÖ for women to study anatomy, especially in the presence of men,ÔÇŁ explains Dr. Murray, noting that QueenÔÇÖs and Harvard did not accept female medical students until after World War II. ÔÇťMost places barred women from entering medical school. ItÔÇÖs so odd because, in the family, it was always women who were providing the care.ÔÇŁ

As Dr. Murray explains, DalhousieÔÇÖs decision to encourage women to pursue careers in medicine was even more remarkable because it was entirely proactive. No women had even applied to prompt them into such a decision. It would be several years before the first women applied but, when they did, they made their mark.

Dr. Annie Hamilton (Class of 1894) was the first female graduate of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School and became known in the city for making house calls on a bicycle. She also took up the study of Chinese language and, in 1903, sailed off to Shanghai to work as a medical missionary. Many other female graduates of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School followed in her footsteps, some of them giving their entire lives and sacrificing their own health to care for the poorest of the poor overseas.

Continuing tradition of leadership and service

The medical school and its faculty members have continued to lead and serve in many ways ÔÇö from galvanizing the emergency response to rescue thousands of injured in the aftermath of the Halifax Explosion, to providing mobile hospital care in Europe on the front of two world wars.

Many outstanding physicians led the medical school ÔÇö and community ÔÇö in important new directions. Under Dr. Harold Benge Atlee, for example, the medical school and teaching maternity hospital (the Salvation Army Grace Maternity Hospital) revolutionized the practice of obstetrics and pre- and post-natal care.

The medical school also took the lead in training nurses and pharmacists. Eventually, of course, these professions established their own schools at Dalhousie, but they got their start at the medical school.

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School has become known internationally for its role in pioneering continuing education for practicing physicians, for its scholarship and advancements in medical education methods, for its implementation of a distributed model of education across the Maritimes, and for leading the way in Canada in interprofessional approaches to educating physicians and allied health professionals together in teams. Recent years have brought state-of-the art research and learning facilities, globally influential discoveries, and important contributions to public policy, the practice of medicine and delivery of health care services.

Dr. Jock Murray with Dr. Allan Marble, chairman of the Nova Scotia Medical History Society.

ÔÇťThe recent history is more difficult to put in context,ÔÇŁ says Dr. Murray, ÔÇťbecause you donÔÇÖt know how current changes and innovations will play out.ÔÇŁ In his book, however, Dr. Murray brings us to the present day. As he writes in his final paragraph:

ÔÇťThe future is uncertain, and the recent dramatic changes in medicine and medical education assure that the future will be very different. But one thing will not change: the commitment of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School to be socially responsible to the broader community. The medical school is poised to be in the forefront of advance in medical education, research, and patient care. The faculty will continue to carry out the noble goals of that small group of dedicated doctors who were the founders of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School.ÔÇŁ

###

Dr. T. Jock Murray (Class of 1963) was the Dean of Medicine at ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°Medical School from 1985 to 1992. In addition to his contributions to medical education, medical humanities and multiple sclerosis research and care, he is a noted medical historian and author of several other books. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia, and an inductee of the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame. He has dedicated Noble Goals, Dedicated Doctors to the memory of his daughter, Suellen Murray, a public relations graduate and health policy lawyer who assisted him tremendously in his research and writing over the years.

Archival photos via Nimbus Publishing.